The Executive Presidency, installed by the 1978 Constitution, has long been identified as the root cause of Sri Lanka’s democratic decline and institutional decay. Described by many as the “bane of the country’s governance failures,” the system has allowed an alarming concentration of power in a single individual, creating an unaccountable office that is both

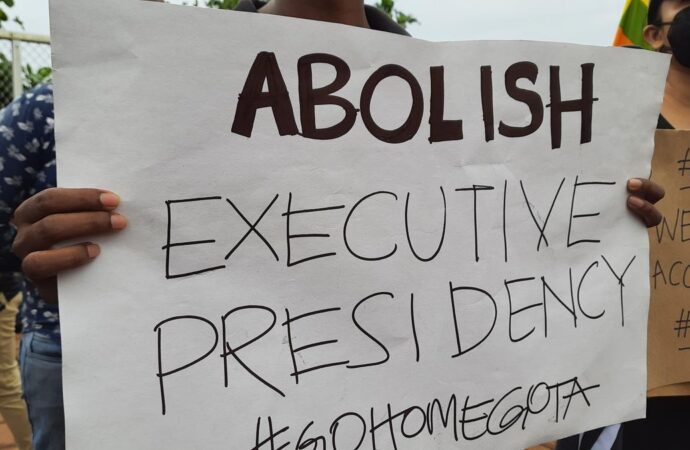

The Executive Presidency, installed by the 1978 Constitution, has long been identified as the root cause of Sri Lanka’s democratic decline and institutional decay. Described by many as the “bane of the country’s governance failures,” the system has allowed an alarming concentration of power in a single individual, creating an unaccountable office that is both undemocratic and dangerous to the country’s long-term stability.

Even though it was the United National Party (UNP) that championed and implemented the Executive Presidency, history shows that the very same party came to regret its creation. Over time, political parties across the spectrum—from the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) to the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), Tamil and Muslim parties, and now the National People’s Power (NPP)—have all formally recognized the urgent need to abolish it. Despite this overwhelming national consensus, the Executive Presidency continues to exist, propped up by shifting political interests and a reluctance to surrender entrenched powers.

A System Rejected by Its Own Architects

It is important to remember that even in the early 1970s, the idea of a presidential system was not new. In fact, J. R. Jayewardene, then the Leader of the Opposition, proposed such a model during the drafting of the First Republican Constitution in 1971–72. But the proposal was rejected outright by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike—who would have been the first to benefit from it—on the principled grounds that it would be unsuitable for Sri Lanka. Her foresight and restraint stand in stark contrast to the constitutional engineering that would follow in 1978 under Jayewardene’s UNP-led government, when the Executive Presidency was formally enshrined.

Veteran leftist leaders Dr. N. M. Perera and Dr. Colvin R. de Silva were among the fiercest critics of the system. They warned of the damage it would do to democratic institutions, minority rights, and governance. History has proven them right. Under the Executive Presidency, Sri Lanka endured a devastating civil war, suffered persistent ethnic divisions, and most recently, experienced the worst economic crisis since independence—marked by mass protests, sovereign default, and widespread suffering.

Power Consolidation and Abuse

The central critique of the Executive Presidency is its excessive centralization of power. It overrides checks and balances, weakens Parliament, and marginalizes local government. It has enabled the politicization of independent commissions, the militarization of civil spaces, and the erosion of public accountability.

Although some curbs have been introduced—most notably through the 17th, 19th, and 21st Amendments—these were either partial or later rolled back. The 18th and 20th Amendments, for example, shamelessly restored and expanded presidential powers for the personal gain of those in office, under the guise of national interest.

A National Consensus—But No Action

Today, the political will to abolish the Executive Presidency is not in doubt—at least on paper. The Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), the ideological core of the NPP, has been among the most consistent critics of the system. Senior JVP/NPP leader Sunil Handunnetti, following the NPP’s landmark victory in the 2024 Presidential Election, declared that Anura Kumara Dissanayake would be Sri Lanka’s last Executive President.

And yet, eight months since assuming office, the NPP-led administration has made no tangible progress on constitutional reform. This inaction raises troubling questions. Is the party unwilling to move because it now finds the powers of the Executive Presidency too convenient to relinquish? Or is it simply biding its time, waiting for the “right” moment?

Either way, delay risks undermining the public’s faith in the NPP’s reformist credentials. More dangerously, it prolongs the lifespan of a system that has already done irreversible harm to Sri Lanka’s democracy.

The Way Forward

If the NPP is concerned about triggering political instability by prematurely stripping the presidency of its powers, there is a clear and democratic solution: begin the constitutional reform process now and complete it as early as possible, but make it effective only after the conclusion of the current president’s term. This would signal a firm commitment to reform without disrupting the current administration’s capacity to govern.

Such an approach would preserve the principle of democratic transition while laying the groundwork for a more accountable, decentralized, and participatory system of governance. It would also send a powerful message to the public, civil society, and the international community that the era of unchecked executive rule is coming to an end.

Conclusion: Abolish Now or Regret Later

Sri Lanka has paid dearly for the concentration of power in the presidency—through civil war, economic collapse, human rights abuses, and deepening social divides. The current moment offers a historic opportunity to correct this course.

If this moment is squandered, the country may once again find itself caught in the cycle of authoritarianism, instability, and democratic backsliding. The NPP must act now, not for political gain, but for the long-term future of Sri Lanka. The Executive Presidency must go—and there is no better time to begin than now

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *